What’s more American than apple pie?

What’s more American than apple pie?

This fall, we had an abundance of apples on our backyard trees. Suddenly, my husband and I had about fifty pounds of sweet goodness to peel, core, and use for yummy concoctions. We made pies, applesauce, dumplings, and apple crisp. We ate fresh apples. We ate dehydrated apple chips. I made apple-cheese-ham kabobs. We froze bags and bags of sliced apples. We carefully maneuvered around huge swarms of bees that would gather as the apples were prepared on our backyard deck.

What else could I do with my apples (besides attract insects)? Maybe I could preserve some apple butter. But the problem is, I am a wanna-be canner, not a knowledgeable one!

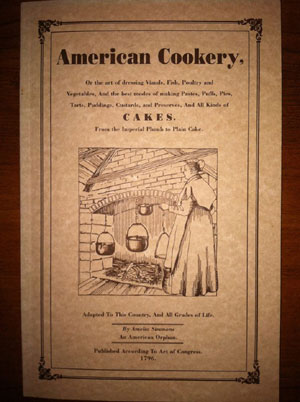

I decided to ask my hippy-homestead-chef-mom about making and preserving apple butter. She couldn’t remember the recipe, but handed me a book and said “look in here.” Now, I’d seen this book on her kitchen shelf before, but never paid attention. The cover had a curiously long title:

American Cookery, or the art of dressing viands, fish, poultry, and vegetables, and the best modes of making pastes, puffs, pies, tarts, puddings, custards, and preserves, and all kinds of cakes, from the imperial plum to plain cake: Adapted to this country, and all grades of life.

Book by Amelia Simmons, published by an Act of Congress.

What the heck is a viand, and what’s up with this strange title on this ancient-looking book? An act of Congress was necessary to get it published?

According to Wikipedia:

“American Cookery, by Amelia Simmons, was the first known cookbook written by an American, published in Hartford, Connecticut in 1796. Until then, the cookbooks printed and used in the Thirteen Colonies were British.”

Ah, so the Americans wanted a cookbook by Americans, for Americans using food available in the new world? That makes sense.

Flipping through the first pages of the book, I wonder if my mom is crazy. This book is written in a manner of old English typography and strange verbiage. It doesn’t even look like a “normal” cookbook with lists of ingredients and directions. Instead, it uses strange descriptions of preparing food, paragraph form, in a manner of fire-baking or cooking almost everything.

Turning to the back of the book, I’m relieved to see a translated version that is much easier to read. Still, this is not like any cooking directions I’ve ever seen. And, while there is no description of apple butter making, there is an interesting paragraph about preserving fruits for tarts or pies:

“Gather them when full grown, and just as they begin to turn. Pick all the largest out, saving about two thirds of the fruit,”(Simmons, 1796, pp. 107). It goes on describe the selection of the largest fruits, covering them in water in a pot, and boiling them. After the fruit is soft, straining them through a “course hair sieve” is recommended (I’m guessing a regular old kitchen-strainer would work fine). After the strained fruit is placed back in the boil-water, a “pound and a half of sugar” is suggested, (I have no idea of the ratio of the apples to sugar, as it’s not specified). Once the sugar and fruit-water is boiling again, the rest of the fruit is added, and the concoction is immediately removed from the fire. When it’s all cool, the contents are poured in to wide-mouthed jars and covered with white oiled paper.

Kept in a cool place, I wonder how long the preserves would keep? I also wonder how often our founding mothers and fathers had food poisoning?

If you’d like to pick up a copy of this interesting book, you can order it from Tresco Publishers in Canton, Ohio. Just look them up on Amazon. They have a number of interesting old cooking and home remedy books that may also interest you.

If anyone figures out what a “viand” is, will you please let me know in the comments below?